In the Rasperry Pi forum, there are quite often questions on how to get a GPIO pin status displayed on a web page.

Common attempts are with CGI scripts; webiopi or other frameworks are proposed. CGI is quite outdated; and complex frameworks handle many technologies under the hood and leave few opportunities to learn.

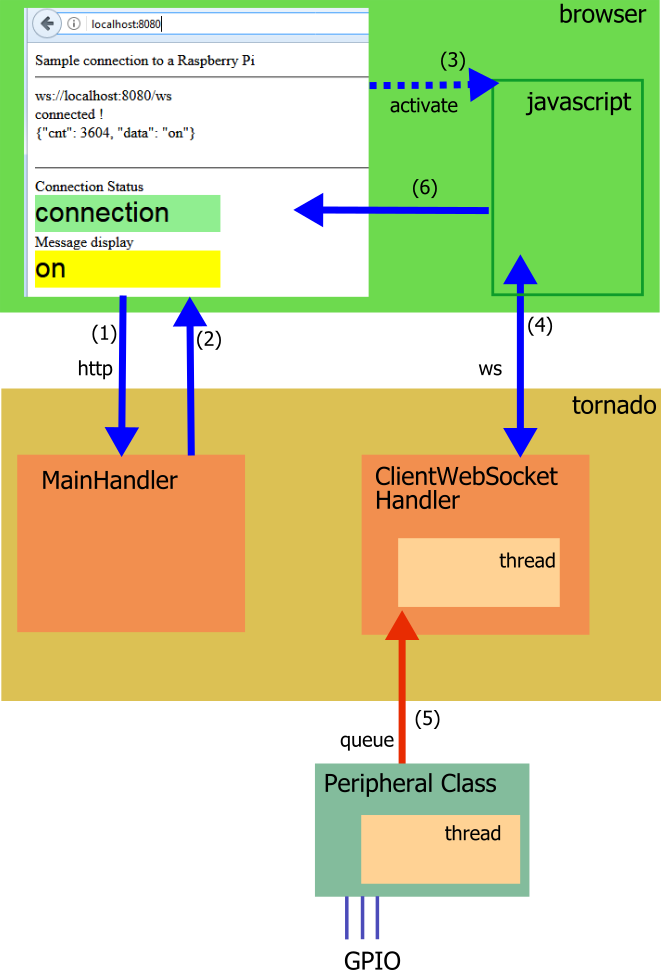

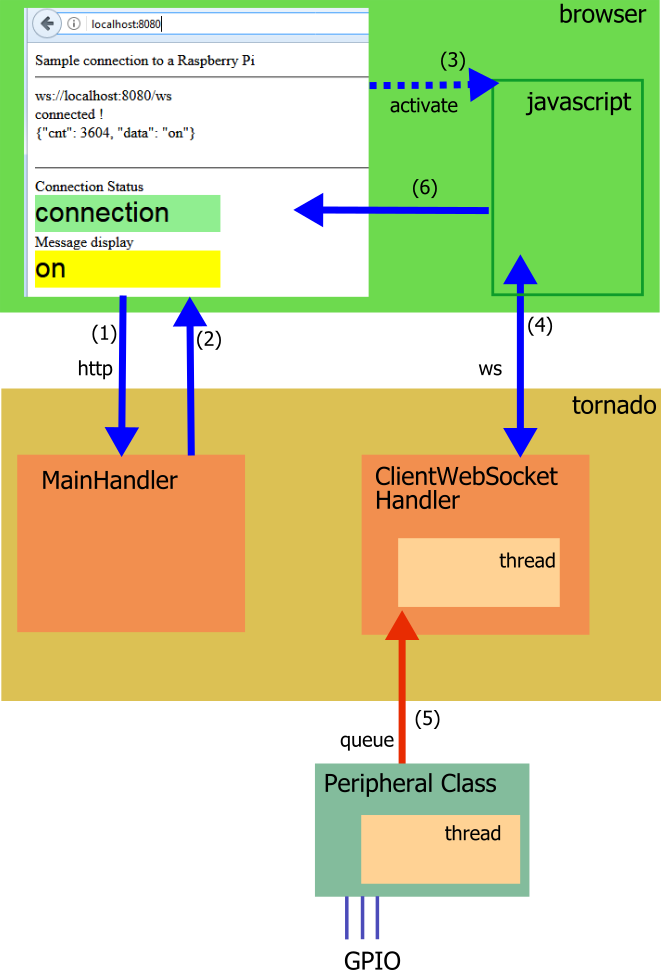

I usually propose an architecture based on a python web application server, using websockets to send events to the browser. The browser uses javascript to display the data. Collection of GPIO events is done in a thread and data are sent through a queue to the python web application server. This architecture can be tested step by step and can be adjusted to different needs.

An overall sketch of the modules shows the connection between the components.

Basic sequence is: (1) Browser requests web page from server, (2) server provides web page and (3) javascript in browser is activated. (4) Javascript opens a websocket to the server. In the server, there are handler for the http request and web socket. The peripheral access is handled in a separate class and (5) sends data through a queue to the web socket handler. (6) in browser, javascript sets the received data into the html-document.

(1) Browser requests web page. The python web application server is responsible to handle this.

(2) To provide the page, the ‘tornado’ package is used. All these web app servers consist of Handler classes for various purpose. The tornado framework uses a mapping from web request pathes to the Handlers.

def make_app():

return tornado.web.Application(

[

(r"/" , MainHandler),

(r"/ws", ClientWebSocketHandler),

]

)

The ‘root’ path for a web page is ‘/’. This is the path a browser requests when http://heppg.de is requested. The http requests have various types, the usual request for a page is a ‘get’ request. The tornado routes this request to the MainHandler, and as it is a get request the method called is the ‘get()’-method.

To tell the whole story, the app server is initialized with

if __name__ == "__main__":

print("start")

app = make_app()

app.listen(8080)

try:

tornado.ioloop.IOLoop.current().start()

except KeyboardInterrupt:

peripheral.stop()

runMessageSend = False

tornado.ioloop.IOLoop.current().stop()

print("stopped")

In this code, there is also the port 8080 in the listen-statement. The url for a browser is

http://localhost:8080

or

http://127.0.0.1:8080

There is extensive documentation on the tornado web site ‘.tornadoweb’.

A basic implementation for the MainHandler is

class MainHandler(tornado.web.RequestHandler):

def get(self):

self.write( "hello world" )

Instead of the simple ‘hello world’ a web page is produced. Html pages are xml structures, containing <head> and <body>-Elements.

class MainHandler(tornado.web.RequestHandler):

def get(self):

self.write( """<html>

<head>

<title>Websocket sample</title>

</head>

<body>

Sample connection to a Raspberry Pi

</body>

</html>"""

The quotation with the three quotes allows to use multiline content, which makes editing simpler.

So far the page contains only the basic elements. As we later need some boxes to add text, these are defined with labels.

"""<html>

<head>

<title>Websocket sample</title>

</head>

<body>

Sample connection to a Raspberry Pi

<hr/>

<div>

<div style="position:relative; width:400px; height:80px;" >

<div id="addr" style="width:400px; height:20px;"> addr </div>

<div id="status" style="width:400px; height:20px;"> status </div>

<div id="msg" style="width:400px; height:20px;"> message </div>

</div>

</div>

<hr/>

Connection Status

<div id="connection" style="position:relative; width:200px; height:40px;background:lightgrey; font: 30px arial, sans-serif;" >

connection

</div>

Message display

<div id="feld" style="position:relative; width:200px; height:40px;background:lightgrey; font: 30px arial, sans-serif;" >

message

</div> ..."""

(3) The javascript part plays its role now. With javascript, websockets can be opened and data can be send to the server or received from the server.

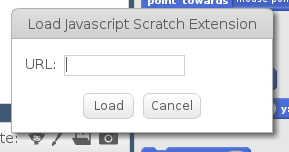

(4) To open a socket, the address needs to be build from the servers address. As the web page is received from the server, this is already known inside the browser context. Instead of http:// as the protocol, the protocol used is ws://. For a local connection, this results in “ws://localhost:8080/ws”. The trailing “/ws” is needed for the tornado routing which addresses this request to the WebSocketHandler.

var addr = "ws://" + window.location.hostname + ":" + window.location.port + "/ws";

var websocket = new WebSocket( addr );

Javascript uses ‘callback’ methods on websocket events.

websocket.onmessage = function(e){

...

}

websocket.onopen = function(){

console.log('Connection open!');

...

}

websocket.onclose = function(){

console.log('Connection closed');

...

}

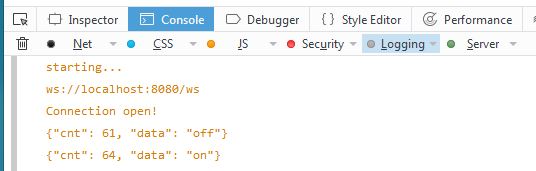

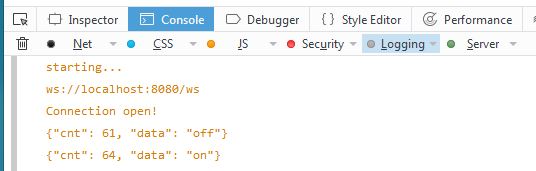

The content is abbreviated … for clarity. The console.log(‘hello’); is a convenient way to debug javascript in a browser. If firefox is used, the debugger is available inside the browser. In earlier releases there was usually ‘firebug’ used, an extension to firefox. In newer releases – here I use 53.3 – firebug is no longer supported and “Firefox DevTools” instead. These are activated with a right click in the page and ‘inspect element’.

Really useful for finding out what the system is doing. Of course the debugger is also sometimes needed.

When the connection is opened, the callback function sets the status color.

websocket.onopen = function(){

console.log('Connection open!');

document.getElementById("connection").style.background = 'lightgreen';

document.getElementById("status").innerHTML = 'connected !';

}

The elements retrieved from the html document are the named ‘div’ sections ‘connection’ and ‘status’.

Next important step is inside the python app server. When socket is opened, an instance of ClientWebSocketHandler is created. In the current application, the class starts a thread which shuffles data from a queue into the send method. So whenever a message is on the queue, this message is sent to the browser.

# a variable to gracefully stop the threadsrunMessageSend = True

class ClientWebSocketHandler(tornado.websocket.WebSocketHandler):

def __init__(self, args, kwargs):

tornado.websocket.WebSocketHandler.__init__(self, args, kwargs)

print("ClientWebSocketHandler.init")

self.my_thread = threading.Thread(target = self.run)

self.my_thread.start()

def run(self):

while runMessageSend:

try:

# something on the queue ?

s = sendQueue.get(block=True, timeout=0.1)

except Exception:

continue

# doublecheck if connection available

if self.ws_connection is None:

print("discard ", s)

else:

print("send ", s)

try:

# and send toward the browser

self.write_message(s )

except Exception:

pass

(5) The other side of the queue can be used as needed. As a sample, here just a debug-Sending class which sends ‘on’, ‘off’ packed in a json telegram.

# messages from Periphaeral Class to Websocket

sendQueue= Queue.Queue()

class PeripheralDebug:

"""Debug class"""

def __init__(self, sendQueue):

self.sendQueue = sendQueue

def start(self):

self.runit = True

blinkThread = threading.Thread(target=self.blink)

blinkThread.start()

def stop(self):

self.runit = False

def blink(self):

cnt = 0

while self.runit:

self.sendQueue.put( { 'data': 'on', 'cnt' : cnt } )

cnt += 1

time.sleep(0.5)

self.sendQueue.put( { 'data': 'off', 'cnt' : cnt } )

cnt += 1

time.sleep(0.5)

The json telegrams “{ ‘data’: ‘on’, ‘cnt’ : cnt }” contain the ‘data’-element and a counter ‘cnt’. It is usually a good idea to pack a telegram counter into a telegram. This helps to find out whether messages are lost or a connection was broken for some time.

The queue is created with Queue.Queue(), which is typical for python 2; in python3 it is more consistent with queue.Queue().

The PeripheralDebug-Class is started with

peripheral = PeripheralDebug()

peripheral.start()

Instead of this debug-Class, a ‘real’ PeripheralGPIO class can be used. When the Telegram is the same, and the queue is same queue as before, this can be exchanged easily.

class PeripheralGPIO:

"""Connection to a GPIO pin"""

def __init__(self, sendQueue):

self.sendQueue = sendQueue

GPIO.setmode(GPIO.BCM)

GPIO.setwarnings(False)

self.channel = 4

GPIO.setup(self.channel, GPIO.IN, pull_up_down=GPIO.PUD_UP)

def start(self):

self.runit = True

blinkThread = threading.Thread(target=self.run)

blinkThread.start()

def stop(self):

self.runit = False

def run(self):

cnt = 0

prev = None

while self.runit:

res = GPIO.input(self.channel)

if prev != res:

if res:

self.sendQueue.put( { 'data': 'on', 'cnt' : cnt } )

else:

self.sendQueue.put( { 'data': 'off', 'cnt' : cnt } )

cnt += 1

prev = res

# for debouncing and limiting number of events per time

time.sleep(0.01)

In IT terminology, these two classes PeripheralGPIO and PeripheralDebug use the same interface. Unfortunately, in python Interfaces are not very prominent. To make this ‘Factory Pattern’ complete, there is also a PeripheralFactory which returns either the debug-version or the GPIO-version of these classes.

class PeripheralFactory:

@staticmethod

def getPeripheral(debug):

if debug:

return PeripheralDebug(sendQueue)

else:

return PeripheralGPIO(sendQueue)

peripheral = PeripheralFactory.getPeripheral(debug)

peripheral.start()

(6) Last step is to display the data from the websocket in the browser, so javascript gets this task:

websocket.onmessage = function(e){

var server_message = e.data;

var obj = JSON.parse(server_message);

document.getElementById("feld").innerHTML = obj.data;

if ( obj.data == "on" )

{

document.getElementById("feld").style.background = 'yellow';

}

else

{

document.getElementById("feld").style.background = 'lightblue';

}

console.log(server_message);

document.getElementById("msg").innerHTML = server_message;

}

The message data are retrieved from the event-attribute data “e.data”. As this message is json, this is parsed with JSON.parse(server_message); returning an object. The data part of the json dictionary is retrieved with obj.data and accordingly the status box is getting its color.

The complete code can be downloaded here.