Siehe auch

Atmel 328-Prozessor als AD-Wandler für Raspberry Pi

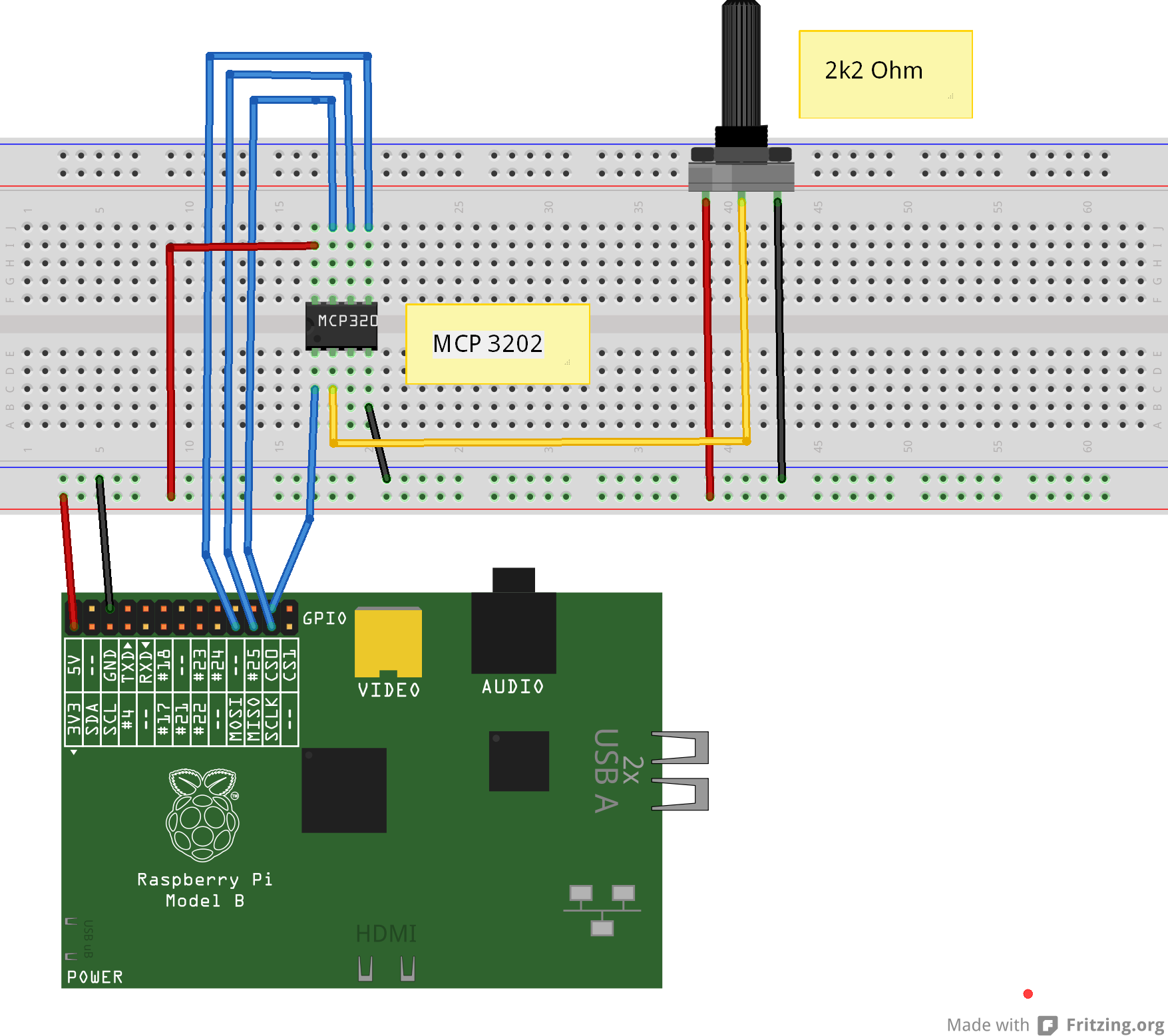

MCP3202-AD Wandler am Raspberry PI

Arduino UNO, NANO connected to Scratch

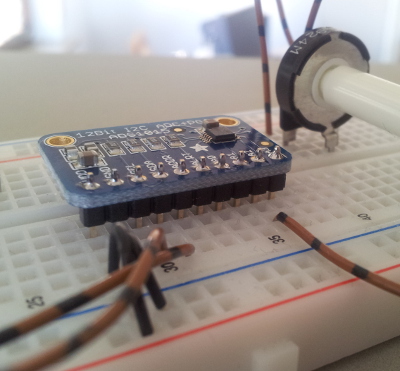

Die Firma adafruit vertreibt eine kleine Platine, die einen 12-Bit ADC ADS1015 enthält. Dieser hat eine eigene Referenzspannung und einen einstellbaren Verstärker. Bis zu 4 Analogkanäle können angeschlossen werden. Der nutzbare Spannungsbereich ist 0 bis 3.3V, da im Beispiel die Platine mit 3,3V betrieben wird.

Diese Platine kann zum Anschluss von analogen Sensoren mit scratch benutzt werden.

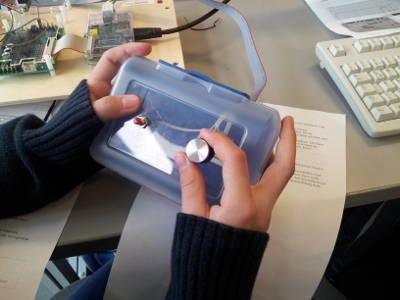

Benötigt: Steckbrett, Lötkolben, Lötzinn, Steckkabel Buchse/Stecker und einige kurze Drahtstücke. Potentiometer 2.2kOhm (hier geht auch bis 10kOhm) als Beispiel für einen Sensor.

Um die Platine an den RPi anzuschliessen ist ein Steckbrett nötig. Die Platine wird ohne montierte Steckleiste ausgeliefert, diese muss selber angelötet werden. So sieht das dann aus.

Um die Platine an den RPi anzuschliessen ist ein Steckbrett nötig. Die Platine wird ohne montierte Steckleiste ausgeliefert, diese muss selber angelötet werden. So sieht das dann aus.

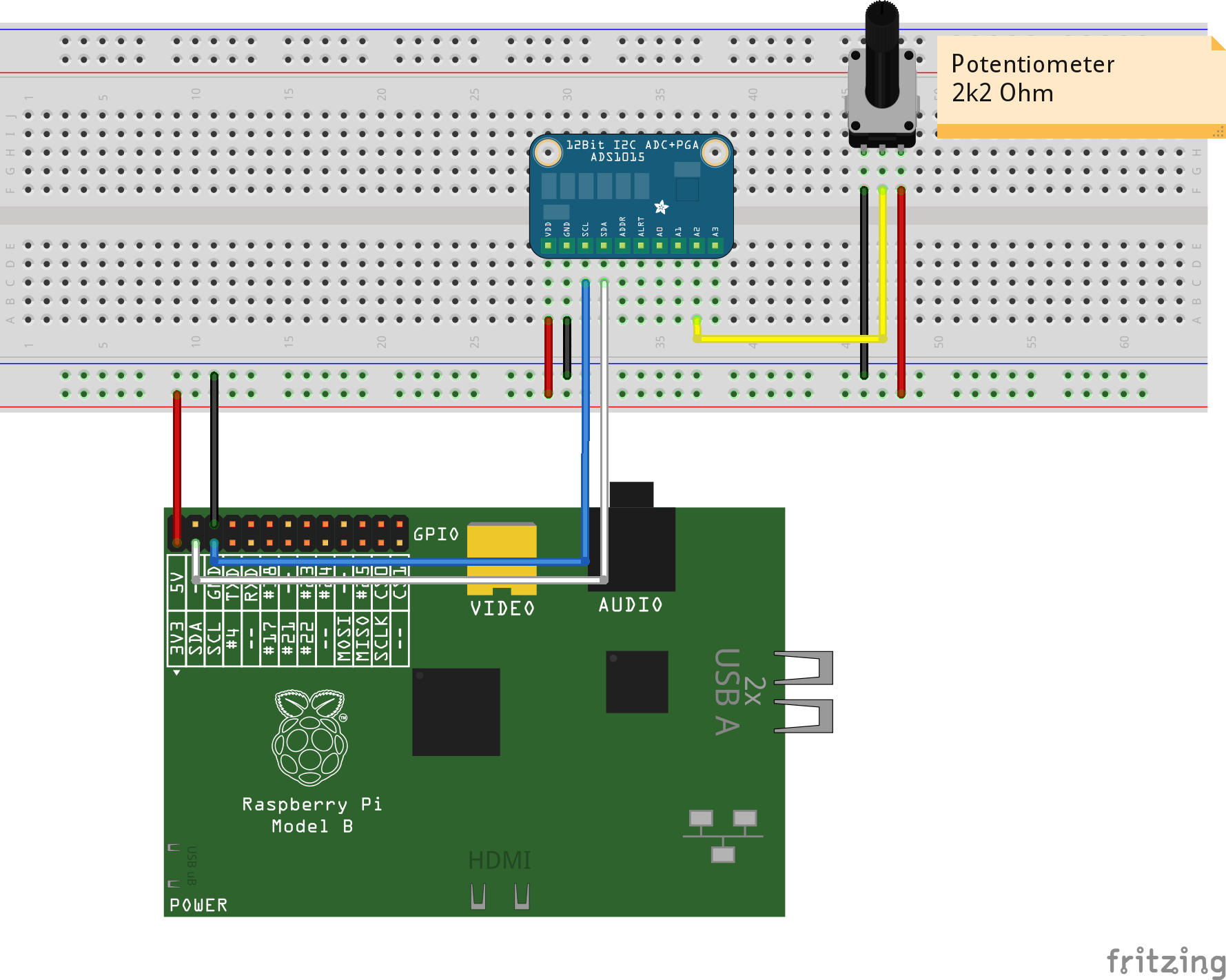

Die Verkabelung ist hier aufgezeichnet.

Hier ist das Potentiometer an den Eingang A2 angeschlossen. Es kann jeder Eingang verwendet werden, das muss dann aber auch in der Konfiguration des scratchClient berücksichtigt werden.

Vorbereitung (siehe auch die Installationsanweiung in der Dokumentation des scratchClient):

sudo apt-get python-smbus i2c-tools sudo modprobe i2c-bcm2708 sudo modprobe i2c-dev

Die ‘i2c-tools’ sind eine Sammlung von Werkzeugen, um den i2c-Bus zu prüfen und Geräte anzusprechen. Nach der Verkabelung kann geprüft werden, ob der Baustein ansprechbar ist.

pi@raspberrypi ~ $ sudo i2cdetect 1 WARNING! This program can confuse your I2C bus, cause data loss and worse! I will probe file /dev/i2c-1. I will probe address range 0x03-0x77. Continue? [Y/n] Y 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 a b c d e f 00: -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- 10: -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- 20: -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- 30: -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- 40: -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- 48 -- -- -- -- -- -- -- 50: -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- 60: -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- 70: -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- pi@raspberrypi ~ $

Der ADS1015 taucht hier mit der (hexadezimalen) Adresse 0x48 im Listing auf.

Start des scratchClient:

cd ~/scratchClient sudo python src/scratchClient.py -c config/config_adc_ads1015.xml

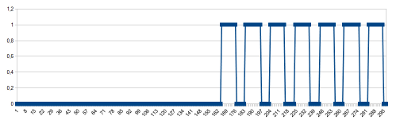

Scratch erhält die Werte vom scratchClient im Bereich 0..3300 (ungefähr) als adc_A2. Das ungefähr deswegen, da der Baustein die Spannung absolut mit seiner eingebauten Referenzspannung misst. Wenn jetzt die 3.3-V-Versorgung der RPi etwas vom Sollwert 3300 mV abweicht, so weicht auch der Maximalwert ab.

Der Name ‘adc_A2’ ist in der Konfigurationsdatei so eingestellt, da im Beispiel der Kanal A2 verwendet wird.